Hello and welcome, reader.

As always, it’s my pleasure to have you join me.

Since launching the new site, I’ve published these things on irregular Saturdays. That’s because many of you work during the week, and I want to give you something to read over a weekend morning coffee.

I still don’t know what to call them.

By now, you also know I favor the essay format here. Though I sometimes stray into a style not unlike the short story. In form, if not content, that is.

Because, you know, I’m a rule-breaker. Either that, or unreliable. Of course, it might depend on who you ask, too.

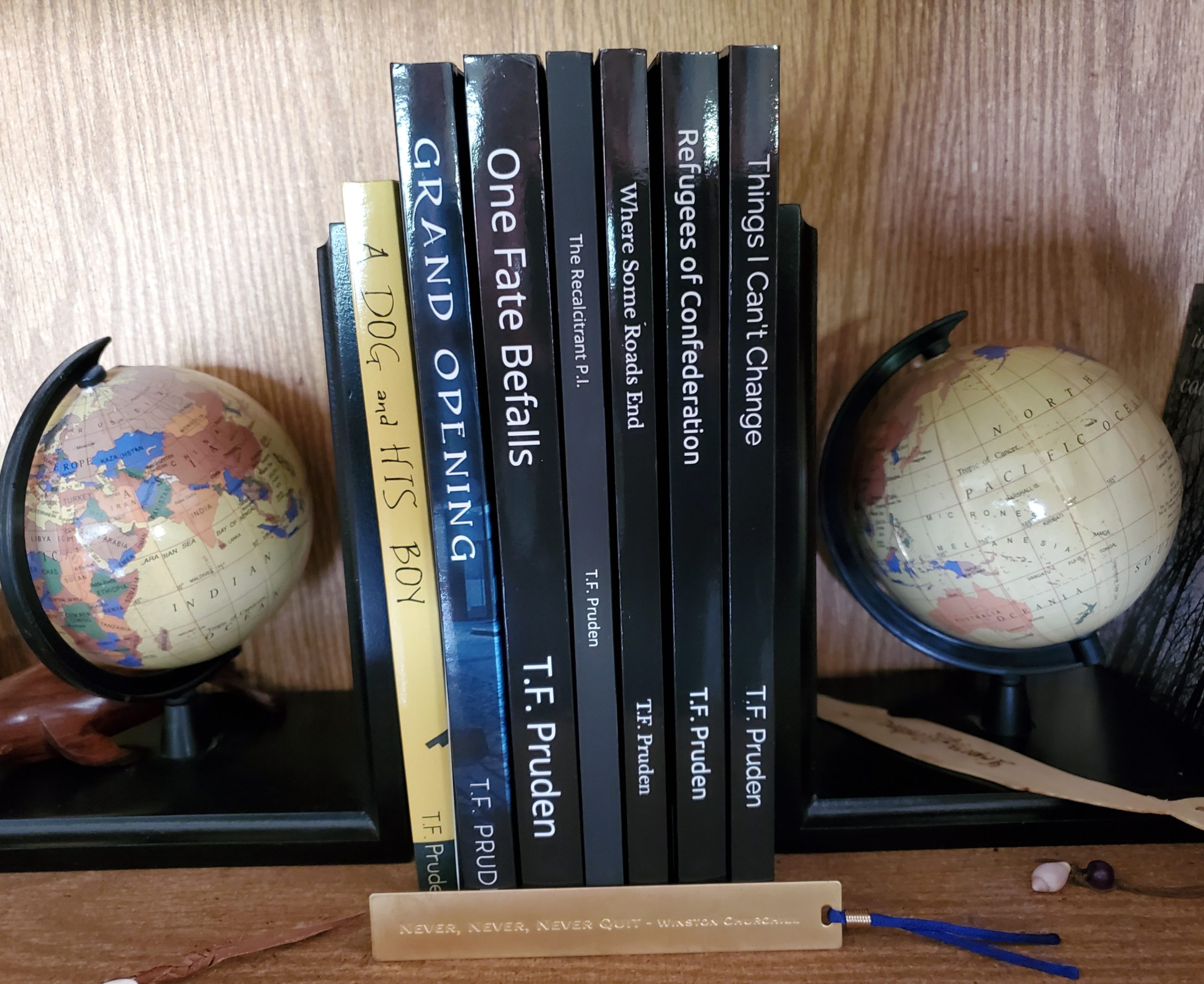

Anyway, this time, my reason for interrupting your weekend is legit. Because my eighth novel publishes next week, on Tuesday, April 15th, 2025. If you’re on the mailing list, I’ll send you an email announcing when the book is available. I’ll send along a URL and invite you to buy a copy, too.

Once again, eBook and paperback edition covers feature a licensed work by Indigenous artist Lonigan Gilbert.

A Whippoorwill Called is the first novel I’ve written as a full-time writer. And I can’t wait for you to read it.

For a preview, click the cover image embedded below here.

Thanks again for your support.

Because writing is a dream for this writer. And every time you read one of my novels, it comes true.

It’s a hell of a deal.

I imagined doing this as a kid. It’s miles beyond satisfying to live it.

So, this time out, beyond the big news, I’m sharing a little history. As usual, I’ll let you decide how much is fact or fiction. For, once again, I’m not sure.

Anyway, for the writers in the crowd, it might be as revealing as any I know. While for everyone else, it could make reading my stuff more fulfilling.

I’ll start with a note about the writing process.

Which, for many of us, remains a daunting challenge. No matter at what point of the writer’s journey, we find ourselves.

Because it’s a solo trip, and the end remains forever out of sight.

There’re no maps, either. And, for me, it turns out full-time effort makes a material difference to the finished work.

That’s a tough one to swallow.

But plain enough, too, when looking back.

That’s because, you know, results speak for themselves. For better and worse. And, in twenty-first century terms, I suck at multi-tasking.

All the same, I wrote my first two novels in between the last few years of Harwill tour dates. In relative terms, the first one proved a minor hit.

I was, of course, encouraged by the early results. And the next spring, when Harwill retired from the stage, believed me ready for life as a writer.

The second one missed the mark.

While I grew ever more dissatisfied with my writing.

And, no surprise, I remained reluctant, too. Of all things designed to limit or constrain my freedom, as either artist or individual. You know, stuff like success and the boundless trappings that come with it.

For I prize independence over all else. And thus, prefer my way over anyone else’s, too, when it comes to spending time. At work, or otherwise.

Despite the preference, my search for trusted advice is near constant. As likewise, those in my circle got sick of the review requests long ago.

However, as they do for everyone, my desires manifest, too. And I’m damned lucky to enjoy independence. Because, for me, that meant writing my next four novels before work, while building a startup company.

In absolute terms, they flopped.

And my dissatisfaction grew with each of them.

For the writing I intended proved beyond my grasp. And with each, I became less sure my talent would ever allow me to achieve it.

The startup’s failure let me write the sixth and seventh novels while working only part time. In between shifts as a writing coach and magazine columnist.

Extra time helped me get closer to the truth.

I was relieved when the sixth one scored another small hit. And thrilled when the seventh made it to third on the minor league charts.

But A Whippoorwill Called is the first I’ve written as a full-time novelist.

Though it’s now a decade since my first novel published.

And getting here took far more than a change of style.

Though that’s plain enough, too, if you’ve read the older stuff. That was the plan, anyway. To show the progress from start to wherever it might finish. And perhaps, to thus share a few of the challenges that lie ahead for those coming along behind me.

More than anything else, I believe that is the way.

For those new to these ramblings, I started as a high school poet.

If you’ve seen the about page here on the website, you’re not surprised to learn I’m now a grandfather.

Anyway, I believe every artist’s life is best viewed as an object lesson. That includes mine.

Now, for an aspiring writer, this next thing is important. I’m lucky to have a small circle of close friends. Many of them are fellow artists. And to them, I owe more than words can say.

This one is big, too. See, I was born into a family rich in arts talent. So, as a boy, I got to see musicians, painters, and writers up close. In the form of both near and distant relatives. Their influence on me and everything I do is plain enough.

To me, anyway.

But some have had more to say about what I do than others. My brothers, without a doubt, had more influence on me than anyone.

I’ve written about them, now and then. And of their influence on me and my work, too. And yes, I know.

I’m blessed. Grateful, too.

Of course, what I believe the greatest blessing to all of us is our children and theirs. Here’s an example of why.

Not so long ago, I discussed my work with a nephew. He’s an emerging artist on Canada’s fine art painting scene. And it’s a rare topic, even when talking with him.

Because my rep for avoiding such talk is well-earned. But I respect both his immense talent and his discerning tastes.

“How goes the latest manuscript?”

When drafting a manuscript now, I write six days per week. On the off days, I like to do a little writing.

Because, you know, I believe in the power of practice.

“Well, I’ve figured something out. But I’m not yet sure. Let’s say I’m optimistic.”

As a writer of novels, meanwhile, my process relies on detailed manuscript outlines. That means I get to know a story quite well, long before writing it.

“You don’t say? And what’s that, anyway, uncle?”

But, and despite my knowledge of countless narrative and character details, I won’t ever know all of it. Not even when it’s done. For as a writer, my first job is getting the parts I know about right. The second is leaving the rest to the reader’s imagination.

You know, the way we must in daily life.

“It’s a synthesis of advanced concepts and simple language.”

Which also means I don’t quite know what I’m doing while I’m doing it. Not if I’m doing it right, anyway. That’s because if I did, I wouldn’t be able to do it at all.

“Well, I look forward to reading it.”

For me, it’s what makes first drafts so much fun to write, too. Despite all of them being destined for an anonymous end.

“Thanks, nephew. I can’t wait to share it with you.”

That, and the idea of granting the only immortality we know to people who earned it. The best and only way I know how.

But not everyone responds to my novels the same way.

“Why the fuck can’t you just tell me a story?”

My younger brother, to whom I dedicated A Whippoorwill Called, spoke via long-distance phone call.

“What do you mean?”

He’s the father of my nephew, the painter. As well as a talented artist and writer himself. And maybe I imagined the frustration in his voice.

Though I have my doubts.

“I mean, you ain’t making music, kid. Enough with the fucking lyrics already!”

I’d be lying if I told you criticism doesn’t hurt. That’s despite enduring a lifetime of it. Because if it didn’t, then whatever I’ve done is false.

“Well, there’s no accounting for taste, I guess.”

Try recalling that the next time someone cares enough to critique your work. Then, embrace the brutal reality of life as an artist.

“Fuck that! Make it like you’re sitting in my head telling me a story! Forget all this grammar and bullshit and make it, so I don’t have to grab a fucking dictionary to make sense of it.”

The words of a brother differ from those of a friend. And, sometimes, they’re more insightful than those of any critic, too.

At such moments, it’s a point worth remembering. Because all good writing is rewriting. And where you start isn’t where you want to finish.

Now, I’m some lucky. That’s for sure. And I know it, too. Because my younger brother spent years in the newspaper rackets. There, he had his best work edited daily. So, that he believes my stuff worth reading is a serious compliment.

His son, meanwhile, is more talented than both of us. It sure looks that way to me, anyway. And younger people reading my stuff is a big part of why I write. Because, though I write about those who were there, it’s meant for those that weren’t.

That’s also why I write about people, neither he nor you, got a chance to meet.

And of times which he was too young to know.

“I’m not sure. But it looks like the peak.”

I’m now at work on the follow up, and the form is holding.

“Only question is how long it lasts. Because the stuff is writing itself, nowadays.”

How’s that for an existential paradox? Well, it’s just like Sam Clemons claimed, I guess. You don’t have to make anything up if you tell the truth.

“You don’t say? Well, uncle, that’s … interesting, I guess?”

His voice reminds me of his dad. It always makes me smile, too.

“Time will tell, nephew.”

I guess knowing those two read them is a big part of what makes writing novels worthwhile for me, as well.

Though it’d be news for me to say that. To either of them, I mean. But like I said before, you know. Blessed.

Now, here’s a little personal philosophy. By that, I mean words by which to live. Which also justifies my taking eight minutes of your precious time.

For here, the words of Aurelius ring true, while failure becomes success. As what stands in the way can only become it.

While doing makes being possible.

Likewise, how becomes clear because of why. For making art is each artist’s attempt to stop time. And pursuing beauty has ever meant finding danger. As sure as chasing truth means accepting a world made of lies.

Because the want for change is a call to act. Just as our knowing more must ever mean we know less. While only living today produces laughter tomorrow. For being you is first a demand to respect others. And there’s no strength in weakness.

From that, I suggest taking what you need and leaving the rest. Know always, too, that my best wishes go with you when you leave this place.

With that, the latest rumination ends.

Thanks for grabbing a copy of A Whippoorwill Called. I’ll look forward to reading your review.

Until next time, thanks for being here, and for sharing this with anyone who might like to read it.

TFP

April 12, 2025